This 31st of August marks the 67th anniversary of the birth of our nation—well, technically, half the nation, as only the peninsula achieved its independence from the British in 1957. Full independence for Malaysia would come slightly over six years later. Nevertheless, the 31st of August will mark the 67th anniversary of the formation of the Federation of Malaya. I’d like to regress a further 10 years to 31 August 1948, exactly 10 years before Malaya’s Independence, when a most dastardly act of terrorism erupted on Penang Island.

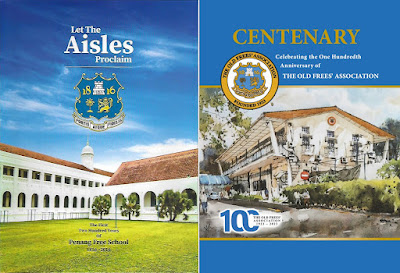

In my 2016 book on Penang Free School, Let the Aisles Proclaim, I dedicated about three pages to discuss this event. Similarly, in my 2023 book on The Old Frees’ Association, Centenary, I repeated much of the same information to a slightly different audience. I wish to share the story again, not in print, but here on my blog, to reach a wider audience who may not have access to my books. In my writings, I described the event as "a murder most foul," and indeed it was.

The most shocking news to emerge in 1948 was the cold-blooded murder of Dr Ong Chong Keng at the hands of an unknown assailant on the night of 31st August. The news rocked the Federation and was carried on the front pages of the newspapers:Dr. Ong Chong Keng, a Federal Executive and Legislative Councillor, was murdered by an unknown gunman in a squatter area three miles from the centre of Penang. Police offered a reward of $5,000 for information leading to the arrest of the murderer. A Chinese youth was detained.Dr. Ong had long been opposed to Communism and had not hesitated to state his views in the Federal Council. He was found dead with bullet wounds in his head at 7am in a lane in a squatter area at Trusan Road, a turning off Perak Road. He had been called out to a case and left his house on a motorcycle. Police were not prepared to state whether the call was real or a fake to get Dr Ong away from his house. He apparently left his motorcycle at Trusan Road and took one of the many footpaths in the kampong. He was found sprawled face downwards with his medical bag close by.An official police statement said that at 9pm a young Chinese youth, aged about 22, went to Dr Ong’s dispensary and told the manager that there was a sick man in Jelutong. The manager contacted Dr Ong, who went on his motorcycle to Jelutong with the young Chinese on the pillion. When Dr Ong had not returned by 11.30pm, the manager went out to look for him but could find no trace of him. He reported the matter to the police, who instructed patrols to make a search for him. Early the next morning, a Chinese man on his way to work saw a crowd of children gathered around a body. A police party identified the body as that of Dr Ong Chong Keng.At the time of his death, Dr Ong was also the President of The Old Frees’ Association. The Free School paid tribute to his memory by flying its flag at half-mast and was well represented by the Scouts at the funeral several days later. In an immediate Government response to the murder, the Commissioner-General, Malcolm MacDonald, said in appreciation, “Dr Ong Chong Keng was a man of rare distinction. He was more than a leader of the Chinese community. He was a leader of the peoples of Malaya. To the service of this country, he dedicated a brilliant array of gifts. He had the courageous heart of a soldier, the cultured mind of a scholar and the noble vision of a statesman. He was a memorable Malayan Patriot.” In a remarkable gesture, MacDonald himself attended Ong’s funeral.A public appreciation was also offered by Harold Cheeseman: “Ong Chong Keng, known to me always as OCK, first came under my notice as a precocious child in Standard II. I watched and indeed stimulated his progress through the school until I had him as a pupil for some years in the top classes. He was not a hard worker. There was no need for him to work hard, for he had exceptional ability. He took a full part, however, in the various school activities and societies. He was a keen scout, later a keen cadet officer, and in after years an enthusiastic volunteer officer. He made his first excursions into debate in the school debating society, and his articles, becoming more and more polished as the years passed, were a feature of the school magazine for many years. From early youth, he was an omnivorous reader, and in recent years there was nothing in which he had greater pride than his library.

"Some pupils pass from the master’s ken after school days are over. Not so with Ong Chong Keng. He maintained regular contact with me throughout his career at the University of Hong Kong and in later years. After the liberation, he never visited Kuala Lumpur without calling on me or writing to express regret if he had been unable to do so. I think, therefore, that I may claim to have known him well. He was an able and forceful speaker. He was ambitious, but it was not merely personal ambition; it was also ambition to be a leader of his people and to work for them. He was proud of being Chinese, but as he used to say to me again and again, he was proud most of all of being a Malayan Chinese."His service was not confined to his community. It was to the country. This was exemplified in many ways. He was a past president of the Penang Rotary Club, and he was an official in, and often the driving force of, many organisations that exist to render service. This true and able son of Malaya has been foully and prematurely cut down in the fullness of his powers, just when life seemed to be opening out for him in great promise. His life was not lived in vain. His service must be an inspiration to all who seek to work for the good of this country.”Police investigations later disclosed that Dr Ong was believed murdered as the result of a conspiracy between the Malayan Communist Party and the Ang Bin Hoay secret society. However, the man that pulled the trigger was never captured. At the inquest in November, an automatic pistol found on the dead body of a Kedah bandit was believed to have been the weapon that killed Dr Ong. A police witness testified that he found the pistol on a hilltop, attached to the body of the bandit, who was believed killed in an engagement with the police and military. One of the five bullets in the pistol’s magazine was sent for testing, and the Senior Chemist concluded he was strongly of the opinion that the bullet matched the one which killed the former Federal Councillor.

In December, the Coroner returned a verdict of “murder by a person or persons unknown” but added that there was good reason to believe that the perpetrator of the crime had outlived his victim for a few weeks and “expired miserably in a place remote from civilisation at the hands of his fellow murderers, his body lying there to rot as would the body of a dead beast of prey.”

The body of Dr Ong was brought to the Toi Shan Convalescent Home on Hutton Lane, where it remained until the fifth of September. After the traditional Chinese funeral rites were completed, a procession of 5,000 relatives and friends followed the hearse on its hour-long journey around George Town. Leading the procession was an armed police escort, accompanied by the Municipal Band, its drums draped in black cloth, playing funeral selections. Following a parade of scrolls and Chinese musical troupes was the hearse, carried by Ong clansmen and escorted by police armed with rifles and Sten guns. Mourners walked beside and behind the hearse, with a contingent of Boy Scouts from local schools bringing up the rear, followed by several thousand friends and relatives. Curious crowds estimated at 50,000 lined the streets, while armed police patrolled the town. Special constables on motorcycles and in loudspeaker vans directed the traffic. The procession dispersed at Macalister Road, after which the hearse proceeded to Mount Erskine for the burial.

No comments:

Post a Comment