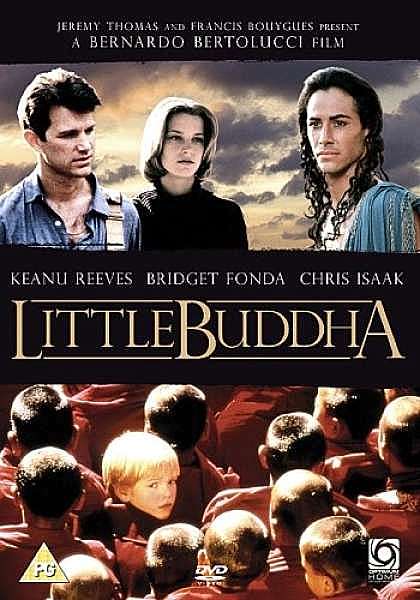

I’ve just watched Little Buddha for perhaps the fourth or fifth time and somehow, it still gets to me. Not in a thrilling action-filled way, but in that quiet thoughtful manner that lingers. Bernardo Bertolucci’s film doesn’t rush. It unfolds slowly and leaves behind a kind of silence that stays with you.

I’ve always found the film fascinating, but then it's because I'm a Buddhist. It weaves together two narratives: the life of Siddhartha Gautama on the path to becoming the Buddha, and a contemporary story set in Seattle about a boy named Jesse Conrad who might or might not be the reincarnation of a Tibetan lama. That latter thread helps guide Western audiences gently into a world they may not fully understand. However, the real magic of the film lies in its treatment of Siddhartha’s journey.The visuals are impressive. India glows with golden and warm earth tones, while Seattle is cool and grey. Bhutan has breathtaking sceneries, notably at Paro Rinpung Dzon: the old monasteries, the monks, the incense smoke rising in slow spirals. Everything felt sacred. In Nepal, the great Boudhanath Stupa in Kathmandu stood out. Mesmerised by the enormous white dome and the all-seeing eyes gazing out in every direction. It’s one of the most important sites for Tibetan Buddhists outside of Tibet.

What impressed me was the care taken to depict the Buddhist rituals. Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, a respected lama in real life, was involved in advising the film. So the mandala offerings, prostrations, monks chanting or the rituals at the monastery felt very real. But I'm sure there's still some artistic licence somewhere, there has to be in any Hollywood film. The Buddha’s teachings are profound and vast, but here they’re trimmed down to a more digestible form for Western audiences. And yet, even with that, the message of mindfulness, impermanence and compassion still comes through. In that sense, the spirit of the Buddhist practice remains intact.

Of course, the film has its limitations. Jesse’s story doesn’t carry the same weight as Siddhartha’s. His parents, especially the sceptical father, came across as stiff and predictable. But I suppose they served a purpose to help translate this vast spiritual tradition into something familiar.

What stays with me every time is that one quiet but shattering moment near the end of Siddhartha’s journey in the film. (And as I write and rewrite the paragraph below with help from AI, I keep adding new knowledge to my own limited understanding of my own religion.)

What stays with me every time is that one quiet but shattering moment near the end of Siddhartha’s journey in the film. (And as I write and rewrite the paragraph below with help from AI, I keep adding new knowledge to my own limited understanding of my own religion.)

Seated beneath the Bodhi tree, he is no longer distracted by Mara’s army of temptations. That part is over. What remains is the final confrontation, not with a demon outside, but with the inner architect of illusion: the ego. Mara asks, “Will you be my god?”, and Siddhartha replies not with resistance, but recognition: “Architect, finally I have met you. You will not build your house again.” The "house" represents the ego that we construct: our mind and body entangled in craving and ignorance; the "architect" is the one who keeps building this illusion by reinforcing the habits of ego, attachments and aversion. In that instant, he sees Mara for what he truly is: not a separate being, but the illusion of self, the false identity we each carry. When Siddhartha touches the earth and says, “The earth is my witness,” he isn’t just rejecting Mara. He’s dissolving the very structure—the "house" or ego—that Mara built. And in that quiet bhūmisparśa mudrā gesture, Siddhartha attains enlightenment.

To me, that was the heart of the film in a single, unforgettable scene. The one moment that spoke loudest in the entire film. It was so simple, so still and yet it carried everything. Siddhartha was not calling upon gods or scriptures. Just the Earth. The world itself. “Let this be my witness,” the gesture said.

That one act said more than any of the dialogues. It wasn’t just about spiritual authority. It was about presence, humility and truth. No performance. No preaching. Just stillness. And in that stillness, something sacred happened. Bertolucci captured that beautifully; maybe, he was a Buddhist at heart.

Little Buddha was just one of many films that have tried to depict and interpret the life of the Buddha. Bertolucci’s version wasn’t the final word, and it was never meant to be. It was not perfect but it opened a door to our understanding and curiosity. It invited us to slow down, to listen, to wonder, to ponder. And maybe, just maybe, to sit still long enough to hear something older, quieter and wiser than ourselves. The film is worth sitting down again to watch a sixth time.

No comments:

Post a Comment