Then came the bombing and machine-gunning of the civilians on 11 December 1941 (Thursday) which left huge swathes of devastation in the Chinese quarter of George Town. Hundreds, if not thousands, of civilians were killed, maimed or sustained serious injuries. In its aftermath, many civilians took to the hills of Ayer Itam and Balik Pulau for safety.

Of those that remained behind in the town centre on 12 December 1941 (Friday), the bombings brought out the worst in people. Amidst a second round of Japanese bombing of George Town, law and order disappeared.On the following night, 13 December 1941 (Saturday), the women and children of the European community were quietly evacuated from the island, crossing over to the mainland to take the train to Singapore and arriving there two days later.There were more quiet evacuations to come. The Malaya Tribune of 20 December 1941 reported the withdrawal of the British Garrison in Penang with a large headline but rather short on detail. All that the newspaper could print was: "In a broadcast talk last night the Right Hon A Duff Cooper, the (newly appointed) British Cabinet Minister for the Far East, revealed that the garrison of Penang had been evacuated. It is not, however, stated when the withdrawal from Penang took place, but it may have been when our forces on the mainland retired to new positions along the Sungei Krian."

However, Sara had noted in his memoir, The Sara Saga, that the garrison had left the island on the 14th and 15th of December, the Sunday and Monday after the first wave of Japanese bombings.

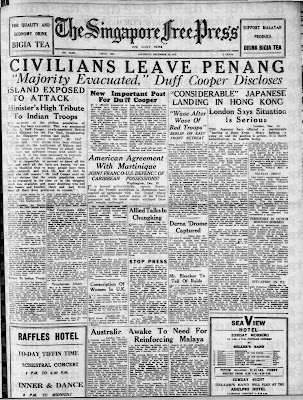

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser held more revelations. In its 20 December 1941 frontpage story, it reported that "the majority of the civilian population of Penang has been evacuated," as announced by Duff Cooper. This statement reeked of the colonial-centric mentality of that time. By "civilian population" he meant only the European civilian population and disregarding the whole Asiatic civilian population who had now been left behind to their own devices. The so-called local population whose pre-Occupation allegiance was largely to the British Crown meant little to him, "The news is grave tonight," Duff Cooper said in his radio broadcast from Singapore. "Our forces have been obliged to retreat in the north-west of Malaya, and as this retreat exposes Penang to attack and we have not sufficient troops with which to garrison it, it has been necessary to evacuate the majority of the civilian population."It is impossible at present to know all the facts and until all the facts are known, we can only be thankful that so many people have been safely removed, and wish the best of luck to those who still remain," he went on. "It was obvious that the whole population could not be evacuated in the time or in the shipping which was available, and many doubtless who had their homes and families there and had lived there all their lives preferred to remain."

Thus it was that on 16 December 1941 (Tuesday), five days after the Japanese attacks, the entire male European civilian population were removed from Penang as well. Saravanamuttu was pretty much incensed when he learnt about the stealth evacuations. "The manner in which it was done was reprehensible in the extreme," he grumbled in his memoir. "No attempt was made to inform the local residents so that they could carry on the essential services of the town. They evacuated Penang secretly by night....they ran away like thieves in the night."

I gathered just as much when writing Let the Aisles Proclaim. I was attempting to uncover information on the impact of the Japanese Occupation on Penang Free School and along the way, also learnt of the fascinating details of the evacuation:The Japanese bombing raids had a devastating effect on the morale of the British residents on the island. On the night of 13th December, there was a quiet evacuation of European women and children. Under stealth of darkness, they travelled by ferry to Prai and boarded the train to Singapore. The following morning, the General Officer Commanding, Malaya, Lt. General A.E. Percival suggested abandoning the defence of Penang. The white flags were raised over Fort Cornwallis, the General Hospital and the Residency, and Penang was declared an open town. In the early evening of 16th December, the ‘white only’ evacuation began of all the remaining European civilians in Penang. Except for a very few of them who chose to remain behind, the Resident Councillor (Leslie Forbes) and his senior officials, as well as the remnants of the 5/14 Company Punjabis and an Indian Army labour contingent, all set off by steamer vessels down the Straits of Malacca to Port Swettenham. (Leslie W) Arnold was never to set foot again in Penang and thus ended his tenure, under the confusion of war, as Headmaster of the Free School.

The bad thing about Penang was its hasty evacuation by the whole of the European population with the exception of two or three who refused to move. The order was given by the military, and the civil Government in Singapore knew nothing about it and would not have approved. This was made quite clear. We should have been able to point out the disastrous effect on morale of such a move. We stood for no racial discrimination (this should also be made clear) and my final telegram to the Resident Councillor dated December 16th read: 'In any evacuation, preference should be given to those who are essential to the war effort, without racial discrimination.' This order to the Resident Councillor came from me, and not from Percival..... Duff Cooper was not in favour of the words underlined, but gave way. On December 23rd I received instructions from the Colonial Office supporting this policy; no other was of course possible if we were to retain any sort of respect.

<< PREVIOUS (PART 2)

<< PREVIOUS (PART 1)

TO BE CONTINUED....

No comments:

Post a Comment